When we think about malnutrition, the first images that come to mind are of a lack or scarcity of food.

In reality, malnutrition, especially in children, involves a number of often overlapping aspects: excessive weight, obesity, “hidden hunger”, growth disorders, and wasting.

Despite the great progress made in developing countries, these phenomena remain widespread throughout the world. At the heart of this problem is a flawed food system that fails to provide children with the diets they need to grow up healthy. And the challenge for the whole world is to change this by adapting to scientifically accepted nutritional standards.

The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) published the report “The State of the World’s Children 2019” with a very significant subheading of “Growing well in a changing world”, which outlines the nutritional problems of the younger sections of the population at the crucial age of growth, both in industrialised and developing countries.

Malnutrition is essentially made up of three distinct components:

Undernutrition continues to affect tens of millions of children. A lack of a proper nutrition, particularly in the first 1,000 days from conception, may result in stunting and prevent children from ever reaching their full physical and intellectual potential. Undernutrition can affect people at any stage in life when there are circumstances such as food shortages and infection, often compounded by conflicts and humanitarian crises.

Hidden hunger comes about from deficiencies in essential vitamins and minerals in the everyday diet. Hidden hunger is dangerous because it is often detected when it is already too late.

Being overweight, especially in its most extreme form of obesity, has long been considered a condition of wealthy and developed countries, but is also now widespread in poorer countries. The cause is related to the greater availability of ‘cheap calories’ from fatty and sugary foods, easily available now in almost every country in the world.

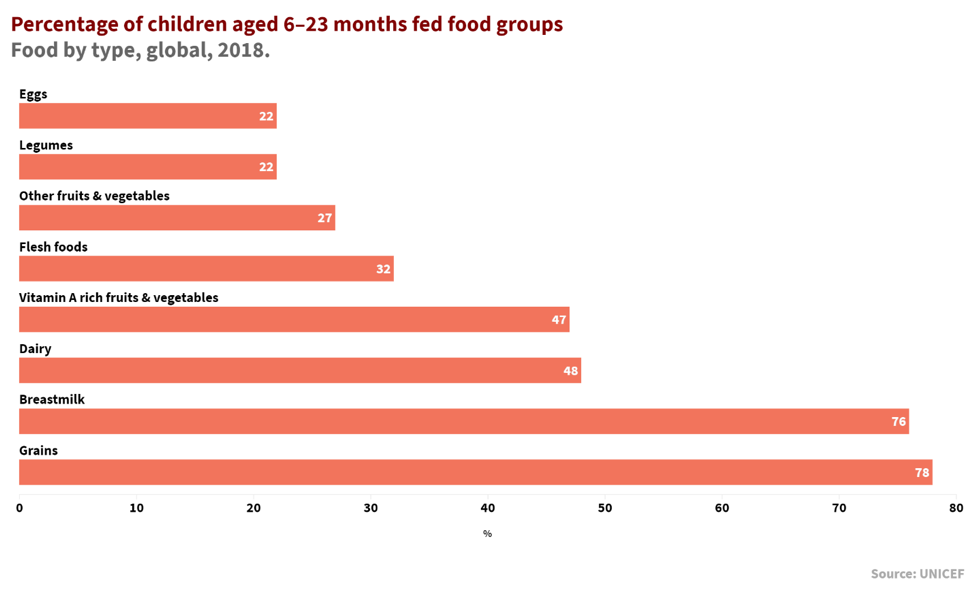

After the first six months, children begin to eat soft or semi-solid foods and need a balanced and diverse diet. The World Health Organization recommends that children this age eat a minimum of five of eight food groups (namely: grains, breastmilk, vitamin A rich fruits and vegetables, flesh foods, dairy, eggs, other fruits and vegetables, and legumes). A lack of diversity in children’s diets can have a devastating impact on their physical and mental development.

In a survey of 72 countries between 2013 and 2018 (with a sample representing 61% of the world population), UNICEF found that 59% of the world’s children are not being fed the nutrients from animal source foods, while 44% of the world’s children are not being fed fruit or vegetables.

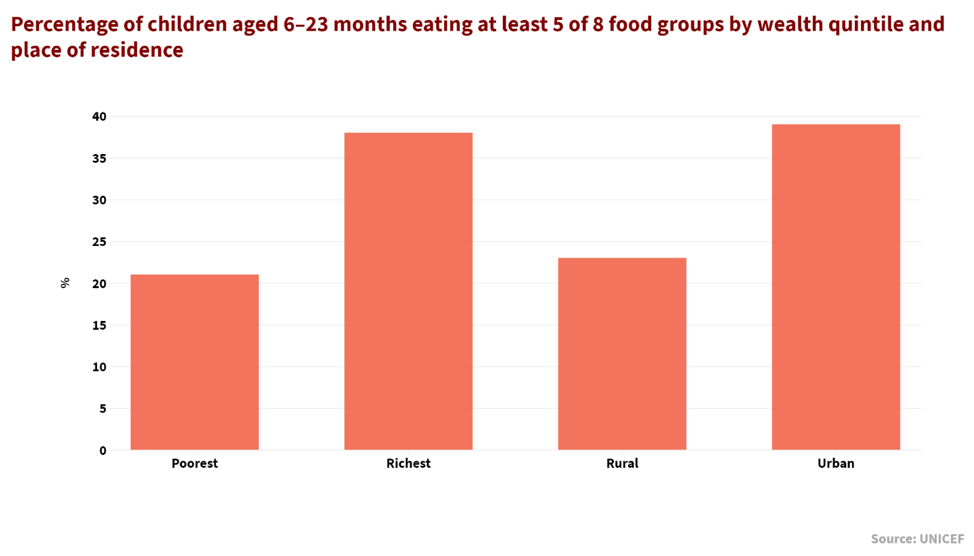

Less than one in three children is eating foods from the minimum number of food groups, and this number falls further when the poorest parts of the planet such as South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka) and East Africa (Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia and Tanzania, among others) are taken into account.

Looking more specifically at the countries, an even more significant difference emerges compared to the purely geographical one. The percentage of children being fed the minimum dietary diversity (5 out of 8 food groups) falls by more than fifteen percentage points if the wealth of the family unit and the place of residence (urban or rural areas) are taken into consideration.

According to UNICEF, the way forward to improve the situation is based on several priorities: first of all, data on childhood nutrition should be collected, analysed and used regularly to track progress and to understand where to direct any policy decisions. Secondly, direct action must be taken with regard to food producers and suppliers, creating a level playing field for everyone and ensuring that their actions are in line with the best interests of children, since the demand for healthy food alone is not enough. It also needs to be affordable, safe and convenient if we want to change the global nutritional landscape. Lastly, actions such as compulsory labelling of the most nutritious foods and protection against less healthy ones should be taken.