24 October 2017

The age of the algorithms

Pros & cons of what some commentators call “Algocracy”

IT codes have taken hold in many sectors, improving our lives and laying the foundations of Artificial Intelligence (AI). However, often they lack transparency and accountability, they are susceptible to biases and have produced effects that even Google and Facebook were not expecting

If the nineteenth century had the novel and the twentieth had television, the years on the cusp of the millennium were marked by the Internet revolution and then in its evolution as Web 2.0. Today, however, there is no doubt that we have entered the age of the algorithms.

What an algorithm is, in reality, is very simple: it is a series of instructions to resolve a problem or a series of problems. A cook’s recipe is an algorithm as is a mathematical equation. Today many fields are governed by codes, which in IT terms make up the text of an algorithm. Think of the finance sector, smartphone apps, programmatic advertising, videogames, in addition, obviously, to search engines, social networks, online maps and e-commerce sites.

Where human intervention is not an option, an algorithm decides. Pedro Domingos wrote in the book The Master Algorithm, “If the algorithms suddenly stopped working the world as we know it would end”.

Aneesh Aneesh, former professor at Stanford University and now at the University of Wisconsin, coined the term “Algocracy” to describe the rise of algorithms and the toppling of traditional hierarchies: algorithms have replaced a typically vertical form of organization governed by procedures from above and with scarce flexibility, with a flexible and horizontal structure. The rule of code is replacing old procedures and it is proving to be a tool to reduce the complexity of the world and serve as a model for interpreting reality.

Furthermore, the development of Artificial Intelligence is based largely on algorithms, on the capacity of machines to learn from their mistakes and to perfect their algorithm (machine learning). In October 2016, in a dossier published online, the White House explained the contribution of algorithms to the development of Artificial Intelligence and the possible effects for the economy. In its conclusions the report posited that, “AI can be a major driver of economic growth and social progress, if industry, civil society, government, and the public work together to support development of the technology, with thoughtful attention to its potential and to managing its risks”. On the topic of risks, the report warned, “automation will end up increasing the salary gap between poorly educated workers and the well-educated, potentially leading to a growth in economic inequality.”

There are no longer doubts about the fact that the development of algorithms has an almost unlimited potential. Last year Google caused a sensation when it announced that software developed by DeepMind, the division of Big G specialized in writing AI algorithms, had managed to defeat the European champion of Go, an ancient Chinese board game.

In an essay published in the law faculty magazine at Columbia University, Michael Gal and Nova Elkin-Koren introduced the concept of “algorithmic consumers”, i.e. the next generation of intelligent digital agents (effectively robots) that will not only do the shopping for us, but will also be able to exchange information and come to agreements on behalf of consumers and negotiate improved conditions with distributors and companies, for example in grocery retail. “The algorithmic consumers have the potential to radically change the way we do business, thus posing new conceptual and regulatory challenges,” write the two scholars.

Recently the issue of algorithms has been raised in relation to fake news, in particular how Google and Facebook intend to clamp down on artificially produced news. In reality, the viral spread of fake news during the last US presidential campaign revealed an aspect that had previously been underestimated: how algorithms often produce effects contrary to the intentions of those who write them. Google and Facebook have admitted ignoring some of the effects produced by algorithms on their platforms. Hence, the partial backtracking and re-evaluation of human intervention (warnings from users, editorial filters) in order to identify false stories and intervene before they go viral.

A growing number of people are requesting greater accountability from Google and Facebook’s algorithms, which - like all industrial secrets - are largely unknown. A book published by Harvard University Press in 2015 The Black Box society. The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information, enjoyed a certain publishing success and ensured that the expression “Black Box” remained in the public debate.

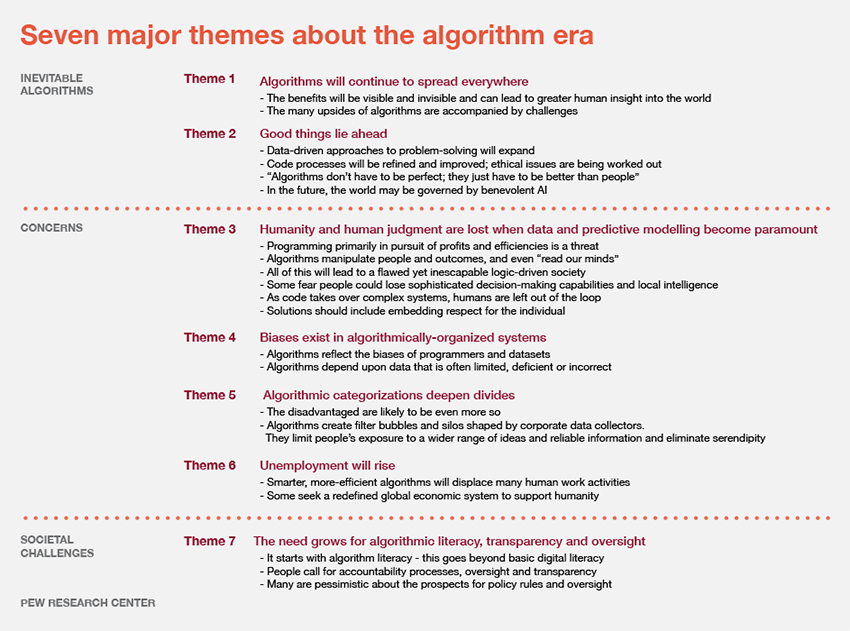

This year the prestigious Pew Research Center published an extensive investigation involving the participation of 1300 experts, managers, university professors and political leaders. The respondents’ verdicts on whether the impact of algorithms is positive or negative is very finely balanced and perhaps this is the real news: 37 % of respondents believe that the negative effects exceed the benefits, while 25% believe that the damage and benefits offset each other. The issue is clearly more controversial than it seems, in spite of the fact that the benefits of algorithms are apparent for all to see.

The authors of the research asked participants also to provide reasons for their opinions and the arguments for and against are summarized in the chart below.

One of the most curious and interesting arguments raised by critics is that of bias (theme number 4), i.e. unintentional prejudice, according to which the algorithm codes are not impersonal and neutral but rather they reflect the ideas, values, ethnicities, gender and social class of those who write them.

“The Hidden Biases in Big Data” is the title of an article written by Kate Crawford, visiting professor at the MIT Center for Civic Media, which this year set up the network AI Initiative, in order to understand and readjust the social impact of artificial intelligence.

Research by Bath University published a few months ago in Science, demonstrated that in semantic machine learning, machines create patterns of existing words but by doing so they reproduce and reinforce the bias of that data. For example, they tend to associate female names with humanistic studies and male names to scientific studies or, in a selection of candidates for a job, they tend to prefer CVs associated with European-American sounding names rather than CVs of those with Afro-American names.

An report by Pro Publica, the non-profit newsroom that produces investigative journalism and is a multiple Pulitzer Prize winner, demonstrated how COMPAS, a software used to identify potential criminals in Florida, in reality hides unintentional prejudices against people of colour. “Machine Bias” was the shock title of the report.