12 January 2017

Great expectations

Indonesian population bets on a new welfare system

Indonesian population bets on a new welfare system

The Indonesian government is ultimately moving away from the long-lasting era of fossil-fuel subsidies. This policy shift could introduce a new welfare system for everyone, even for the small fisheries in the Moluccas.

Until not long ago, the livelihood of a farmer in the island of Java was dramatically bonded to seasonal changes. Scarce precipitations meant droughts; excessive ones depleted the farming fields by turning them into swamps. Even for the fishing communities of the Moluccas, four thousands kilometres East from Java, livelihood insecurity seems to be inescapable. Scarce fish equated low revenues but, paradoxically, even with an abundant catch the result was the same: “Even if in our seas there are prosperous periods where you can just immerse the nets and fish kilos of garfish, catching too much fish is simply a waste of energies. Without a fridge–explains Cosmas, a fisherman of the small archipelago of Kai- the fish will eventually be spoiled. There is no point in catching it in the first place”.

These difficulties related to the poor delivery of services, to the lack of technological advancements and to the inadequate governmental subsidies to fisheries and farms are further aggravated if considered alongside a precarious and overly-expensive health system: from the various rural areas across the country it was often necessary to travel for several kilometres before encountering health facilities able to deliver the needed services.

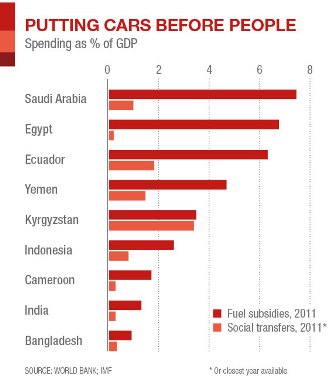

The only benefits that the Indonesian government was delivering to its extensive population, the majority of whom lived –and, to some extent, still does- with an extremely low income, were national subsidies aimed at preventing price volatility of certain goods: rice, for instance, but also fuel. These welfare policies were sustained and carried out for decades through national projects, targeting particular strata of society for a pre-determined period of time. The outcomes were poor and, overtime, not efficient. In fact, as the International Institute for Sustainable Development highlights in his assessment of Indonesian welfare, fuel subsidies cannot work without an efficient national infrastructure: if the roads are uneven and with low maintenance, fuel subsidies will eventually be useless.

Over the last years, things have changed. Starting in 2009, the legislation has introduced a new set of efficient social policies, and, the various Indonesian governments that have succeeded one another have slowly started to move away from national fossil-fuel subsidies policies and targeted projects, recognising their inability to yields efficient results.

The effective turning point however was two years ago. It is obviously too early to assess its impacts and its outcomes, as well as to profound a judgement of how Jakarta has been managing it. For its supporters however, we are now witnessing a proper revolution that, quantitatively speaking, embodies the most spectacular operation in the history of transitional economies moving out of poverty towards a new stage of development.

To be precise, we could point to November the 3rd, 2014 when the neo-elected president Joko Widodo (also referred to as Jokowi) inaugurated his mandate by launching an ambitious restructuring project of Indonesian welfare. The project is grounded upon three fundamental bedrocks: the Welfare Family Savings Program (PSKS), the Indonesian Smart Card (KIS), and the Healthy Indonesia Card (KIS). Joko Widodo’s project was highlighted in the British economic magazine The Economist: a particular mention was directed towards praising the Jokowi himself for being possibly able to accomplish his aims ahead of time: «Barak Obama –writes the Economist- signed his health-care programme into law 427 days after taking office. Joko Widodo, (…) took just two weeks to begin honouring his health-care and education promises»

So, what does Joko Widodo’s project really comprise? The three proposed national schemes provide free health insurance to all Indonesia’s poor and the guarantee of 12 years of free schooling and tertiary education to students admitted to university. They further incorporate cash transfers to poor Indonesians to transition out of the subsidy economy. Widodo’s innovative actions have been financed with the savings derived from the gradual removal of national subsidies on fuel and diesel, capitalised both in delivering services as well as in financing infrastructural innovations as to foster investments. These measures altogether are targeted to reach a net growth of 7% per annum, a rate lastly registered in the mid-1990s. Whether such goal will be met remains to be seen. What can already be seen however is the extensive support that the Indonesian president has been able to provide to over 86 million Indonesians, roughly a third of the whole population.

Widodo’s detractors claim that these schemes will, above all, strengthen the power of the State, further legitimising its invasiveness. Representative of this belief is Jhon Riady, professor of law and executive dean of Indonesian UPH business school, who has opposed Widodo’s policies on the ground that they might favour corruption and foster a sub-optimal allocation of resources, ultimately leading to economic inefficiency.

The president’s supporters instead applaud these new policies as possible means to tackle widespread inequalities between different strata of society, posing particular emphasis on the beneficial effects that they will yield for the large Indonesian informal sector. Regarding State’s invasiveness into the everyday life of its citizens, the ministry of health, Nila Moeloek, has claimed that public health expenditures will proceed hand in hand with private initiatives, such as developing private health insurances.

Jokowi’s solutions are not new, untested, attempts but rather the development of previous experiences: during his mandate as governor of Jakarta he had introduced the Healthy Jakarta Card (KJS), granting free access to health services and the Jakarta Smart Card (KJP), providing subsidies to pay for scholastic fees of needing students.

Thus far, whether Jokowi’s bet will be successful or not is a moot question. What is sure however is that in a country with over 30 million people still living under the poverty line it will not be an easy bet to win.