New Forms of Trade

Trump’s tariff policies marked a clear departure from multilateral rules, creating significant global uncertainty. Meanwhile, the EU seeks new foreign markets as the conflict between the U.S. and China intensifies

THE CONTEXT

The article examines global trade through the lens of Donald Trump’s recent tariff policies.

The Global Trade Turnaround

The new direction of US trade policy under Trump’s second administration marks an endpoint to decades of trade liberalisation. The introduction of reciprocal tariffs in April 2025 raised the average US tariff to levels unseen since Smoot Hawley Tariff Act, even for close partners like the EU. This policy was initially presented as corrective to the US trade deficit, which is large by international comparison and perceived to disadvantage domestic industries. With increasing prominence, the measures are also justified and framed in national security terms. This discretionary and protectionist use of trade policy has signaled a clear move away from long-standing multilateral norms. Europe now faces a new period of uncertainty in global trade, in which it will not only be affected by its relation to the US, but also the evolving trade relations between the US and China.

The imposition of US tariffs on European goods represents a paradigm shift in the trade relations between the EU and its largest partner. For decades, the average US tariff on all imports had been on a downward trend, with tariffs of EU imports reaching 1.47% in 2023. In the negotiations following the liberation day package, which imposed a 20 percent reciprocal tariff on goods from the EU and higher levels for steel, aluminum and cars, Commission President von der Leyen and President Trump agreed on a 15 percent ceiling on tariffs for all products, in addition to a separate 50 percent rate for steel and aluminum. While this is lower than the reciprocal tariffs and the threatened 30 percent if no deal had been reached, it still represents a tenfold increase.

Although this deal offered much-needed clarity and predictability for European businesses, considerable detail has yet to be defined. The $600bn EU investment pledge leaves much room for interpretation, and the agreement is not legally binding in its current form. As legal and political challenges to the tariffs with potential implications for the EU-US relationship continue, the agreed rate may not yet be final.

NUMBERS

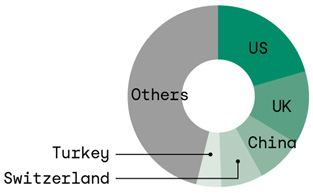

EU Exports

(Source: Eurostat)

46.1%

Others

4.3%

Turkey

7.5%

Switzerland

20.6%

United States

13.2%

United Kingdom

8.3%

China

EU-US trade and the EU economy

Understanding the economic significance of these evolving negotiations requires examining how important trade with the US is for the EU. Importantly, a significant vulnerability for the EU would be an excessive reliance on the US as an export destination. A way to assess this is by looking at the EU value added embedded in US final demand, which captures the goods and services produced in the EU that are ultimately consumed in the US.

OECD numbers indicate that about 20 percent of EU value added in foreign final demand is linked to the US. But the bulk of EU exports are spread across many other countries, including a high share of medium- and high-income economies. This means that while a decrease in US demand does matter, the EU has a strong and diverse network of trade partners in the rest of the world. This decreases its reliance on any single market. Developments in the US alone, as important as they are, should not be enough to critically undermine the European economy.

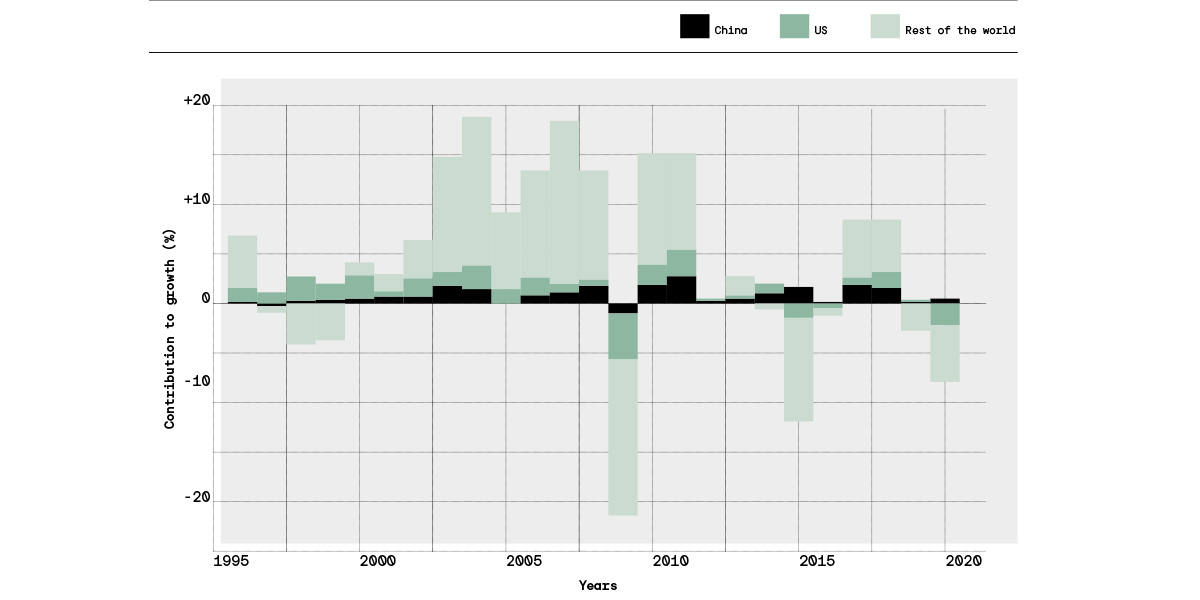

An even more telling perspective is to look at the contribution of different foreign markets to EU export growth. This shows how demand from different trade partners drives increases or decreases in EU exports over time rather than in a single year. It is also an indicator of different countries’ role in supporting export-related economic growth in the EU. Figure 1 shows that, while the US market has been a notable factor in the last two decades, the vast majority of EU export growth can be attributed to trade with other parts of the world. In other words, increase in demand from these countries has been far more important for the EU than demand from the US alone.

AN IN-DEPTH LOOK

US trade

In July 2025, the U.S. trade deficit stood at $78.31 billion. The United States primarily imports and exports goods to and from Mexico, Canada, and China. Among the top American exports are aircraft components and oil, while computers and automobiles rank among the main imports. The largest import growth in July 2025 came from Taiwan, Vietnam, and Switzerland. In the same month, exports increased to Italy, France, and Taiwan.If anything, this implies that the EU can and ought to continue deepening its trade relationships beyond the US. The ongoing talks by the European Commission with key partners including India, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines, as well as the new progress on ratifying the Mercosur agreement, are a recognition of this priority. The challenge now is to ensure these deals translate into real opportunities for European firms.

Nevertheless, the tariffs can be expected to impact different EU regions unequally. Some regions with a higher concentration of pharmaceutical and automobile industries are likely to be affected more strongly than others. These industries represent a significant part of the EU economy and trade more heavily with the US compared to other industries. Areas that can expect to feel the direct impact of the trade deal the most are Ireland, Denmark, and a number of regions in Germany and Italy. The EU will need to adopt sector-specific approaches to mitigate the impact on businesses and employment in these areas.

The impact of tariffs will vary across Europe, with Ireland, Denmark, and parts of Germany and Italy among the regions most at risk

NUMBERS

Figure 1

US and China decoupling

The new US trade stance is not only reshaping relations with Europe. It has also intensified the long-running trade conflict with China, bringing the world’s two largest economies into direct confrontation. For Europe, this adds another layer of risk and uncertainty, as the outcome of US–China tensions will inevitably spill over into global trade.

Political escalation between the two economies has driven the average US tariffs on Chinese imports to 135.3 percent and Chinese tariffs on US imports to 147.6 percent, according to a study from Peterson Institute for International Economics. Following the meeting between Trump and Xi in South Korea, Washington has now announced a reduction in certain tariffs. The outcome of this trade war remains uncertain. In a scenario where the United States and China continue to decouple, global trade patterns could shift in ways that directly involve the EU. Supply chains may need to adjust, and trade flows could move in different directions than today.

For the EU, two main effects are of concern. First, Chinese goods that once entered the US market could be diverted to other destinations, including the EU. An increased inflow of Chinese products could heighten competition for domestic industries and put pressure on local producers. The impact would vary across member states, depending on the degree to which their domestic production overlaps with the Chinese goods being redirected. Germany, with its large motor vehicle sector, would likely feel this most strongly.

At the same time, a greater inflow of Chinese goods could also have a deflationary effect, as the increased supply of certain goods would put downward pressure on prices. This could lower prices for European consumers.

Second, a decoupling could create opportunities for the EU to substitute some of China’s exports to the US. For goods produced in both China and the EU, a higher tariff on China will make EU products comparatively cheaper and more competitive. This could allow EU industries to capture a larger share of the US market. To some extent, this substitution effect could offset, or at least soften, the impact of the tariffs on the EU.

In either case, the uncertain relationship between China and the US may already encourage a gradual shift in trade flows, as businesses prepare to face any type of outcome between the two countries. For the EU, this means preparing for both the risks and the opportunities such shifts could bring, while keeping a realistic sense of their scale within the broader global market.

Future Outlook

The abrupt change in US trade policy begs the question whether the tariffs are here to stay. Here, it is worth tracking several key developments. First, the economic consensus is that the tariffs will impact US GDP the most. Moreover, price pressures on consumer products resulting from the tariffs are likely to be felt very directly by the US electorate. Recent political efforts challenging the autonomy of the Federal Reserve may worsen this further. Together, this creates political pressure to shorten the lifetime of the tariffs.

At the same time, the tariffs already provide a steady stream of revenue to the US government. This may be difficult to replace, if not economically then at the least politically – it should be recalled that the tariffs put in place during Trump’s first term in office were not removed by the Biden administration. This may create a basis for a long-term or permanent introduction of trade barriers between the US and the rest of the world.

As little certainty exists on this question at the present moment, Europe will need to stay agile while adapting to developments in the US as well as China. Currently, the impact on the European macroeconomy is likely to be limited, and yet EU supply chains will already need to adjust. The EU already has valuable trade relationships beyond China and the US. By expanding access to these markets and disclosing new ones, the EU can provide security to its people and business while acting as a champion for rules-based trade.

Madalena Barata da Rocha

Economist, she is a research assistant at the think tank Bruegel. She has also worked as a consultant, focusing on financial sector regulation and public finance management.

Nicolas Boivin

Economist, he served as a research assistant at the think tank Bruegel, following a period at the Swiss Embassy in Ireland, where he dealt with trade-related issues.