Building a World of Beauty, Diversity, and Wonders

Writer David Quammen highlights the similarities between COVID denial and climate denial, warning of a future that could be “duller” and poorer in biodiversity. Embracing a multidisciplinary approach will be essential to safeguarding both the environment and public health

Illustrations by The Archives and Special Collections Department of Dickinson College

Chameleon

“OUR LIVING WORLD,” A NATURAL HISTORY. DI REV. J. G. WOOD. REVISED AND ADAPTED TO AMERICAN ZOOLOGY BY JOSEPH B. HOLDER. VOL.V NEW YORK: SELMAR HESS, 1898.

THE CONTEXT

Quammen explains how science communication and journalism are central to mitigating environmental disasters.

At seventy-seven years old, after tirelessly traveling for work and pleasure, David Quammen has come to a bitter conclusion: we are turning the Earth into a place that is uglier, more monotonous, and more dangerous than the “version we inherited from our ancestors.” The blame, according to the American writer and science communicator, lies in a widespread collapse of wealth — understood here as variety and heterogeneity — caused by two interconnected crises: climate change and the loss of animal, plant, and other forms of biodiversity.

Quammen is well known to the general public for his work on zoonoses, diseases caused by viruses transmitted from animals to humans. This “spillover,” which is also the title of his most famous essay, will become increasingly likely due to the deterioration of natural resources and a wide range of behaviors humanity seems unwilling to abandon.

To reverse this trend, the 1948-born essayist explains, patience is necessary, and we must start again with education: “We need to teach children that science, literature, music, art, and technology are all facets of the most beautiful thing humans have gifted to this world: culture.” Only in this way can we recover the beauty and wonder that we are relentlessly losing, while simultaneously making Earth a safer planet.

Is it fair to say that with your book “Spillover” (2012) you “predicted” Covid? This phrase is often used to describe your work, but – in my view – it undervalues the scientific merit of the book. Science doesn’t rely on a “crystal ball”; it relies on data and rigor to analyze reality and understand its possible trajectories. Do you agree?

Yes, to say I “predicted” the Covid pandemic gives me too much credit for prescience (and perhaps not enough for careful listening to scientific experts). There was nothing surprising, to those who have studied emerging viruses, about the fact that the first major pandemic of the 21st century would be caused by a novel coronavirus, probably after it emerged from a bat, passed through an intermediate wild animal that was sold live for food in a crowded Chinese market, and from there spilled over into humans. Some of the scientists I interviewed in 2007-2010 told me, in various forms and pieces, that exactly such a scenario had high probability, given the nature of what they knew about RNA viruses and about all the human behaviors (including capture and sale of wildlife for food) that give such viruses opportunity to pass into humans.

Papio Leucophaeus

“THE NATURAL HISTORY OF MONKEYS”. ILLUSTRATED BY THIRTY-ONE PLATES, NUMEROUS WOOD-CUTS, AND A PORTRAIT AND MEMOIR OF BUFFON, DI SIR WILLIAM JARDINE, BART. EDINBURGH: W.H. LIZARS, AND STIRLING, AND KENNEY [ETC.], 1833.

The term “Pandemicene” is increasingly used. What do you think of it? Is that the direction we’re heading toward?

I don’t like the term “Pandemicene” because it seems to me a trendy effort to offer a pseudo-paleontological perspective on what is indeed a very important—but not the only important—aspect of current Earth history and ecology. The term “Anthropocene” seems to have taken hold, and now someone wants to better that with another? We don’t need that cleverness-attempting neologism in order to alert people to the dangers of emerging viruses and other pandemic threats.

AN IN-DEPTH LOOK

Spillover

Spillover, or cross-species transmission, is a natural process in which an animal pathogen evolves and becomes capable of infecting humans. Viruses, through genetic mutations, can gain new abilities, including recognizing human cells and replicating within them. This occurs more frequently in RNA viruses, such as coronaviruses, which are generally more prone to acquiring the ability to infect human cells. Cross-species transmission typically happens after prolonged contact between humans and the animal carrying the pathogen.

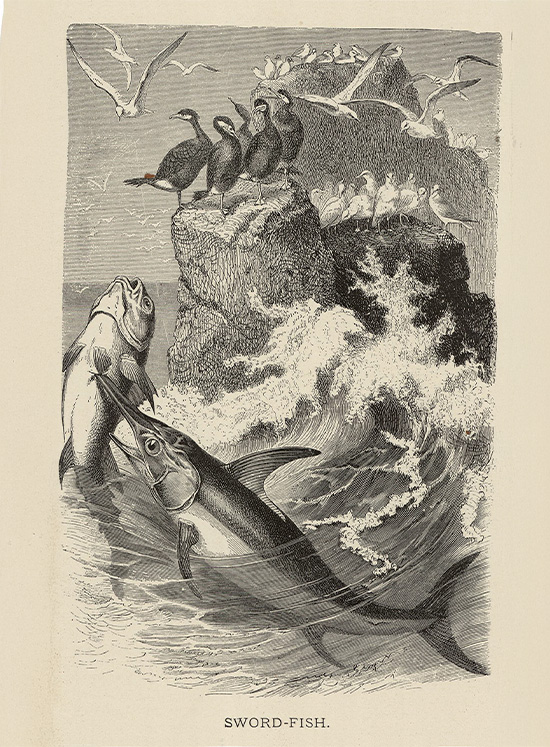

Sword Fish

“OUR LIVING WORLD,” A NATURAL HISTORY. DI REV. J. G. WOOD. REVISED AND ADAPTED TO AMERICAN ZOOLOGY BY JOSEPH B. HOLDER. VOL.V NEW YORK: SELMAR HESS, 1898.

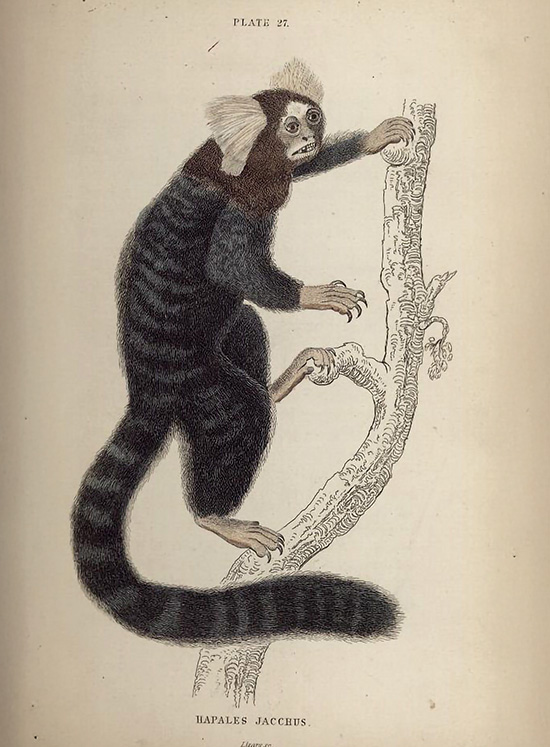

Hapales Jacchus

“THE NATURAL HISTORY OF MONKEYS”. ILLUSTRATED BY THIRTY-ONE PLATES, NUMEROUS WOOD-CUTS, AND A PORTRAIT AND MEMOIR OF BUFFON, BY SIR WILLIAM JARDINE, BART. EDINBURGH: W.H. LIZARS, AND STIRLING, AND KENNEY [ETC.], 1833.

In your view, how has climate change denial evolved in recent years?

Climate change denial has been going on for as long as scientists have been warning (since the late 1970s) about what was once labeled “the Greenhouse Effect” and is now called climate change. People have resisted the warnings because 1) they didn’t comprehend the science in any depth, 2) because it was inconvenient for ordinary people to recognize that our individual actions contribute to damaging changes on Earth, and 3) because fossil-fuel-supply companies and other associated industrial for-profit enterprises saw correctly that widespread adoption of mitigation efforts would decrease their profits.

But now, in recent years, climate-change denial is much worse than ever, riding the crest of a broader trend of science denialism driven by political opportunism and willful public ignorance.

What are the similarities between Covid denialism and climate change denialism?

Confusion, laziness, indifference, fear of intellectual challenge, political polarization of important problems, lies and opportunism by political and business leaders. Also, failure to adequately and engagingly educate young people, beginning around age 10, about science.

Do you think a communication strategy more focused on solutions could help people better grasp the urgency of the climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis?

Not necessarily. To argue, as some do, that communication to the public about climate change and the biodiversity crisis should be “focused on solutions” overlooks the fact that explicating causes and mechanisms of change is just as important as offering solutions. The divide between those approaches involves the fact that such problems are widespread and global, whereas many of the solutions must be individual and local.

What are the key factors to improve communication and collaboration between scientists and journalists? During the Covid pandemic, this communication often failed, and that contributed to the spread of skepticism toward scientifically agreed-upon solutions.

Scientists must explain to the public not only what science says, but also what science is, how it works, how it evolves, and how it quickly corrects its mistakes. This qualitative leap is possible thanks to an increase in research funding. The public needs to do a better job of being curious. Educators, with the support of parents, need to do a better job of educating young children about science. And I, along with all my colleagues in the profession of science writing and reporting, need to do a better job of bridging the gap between scientists and the public.

Scientists must explain not only what science says, but also what it is, how it works, and how it corrects its own mistakes. More funding for research is also needed

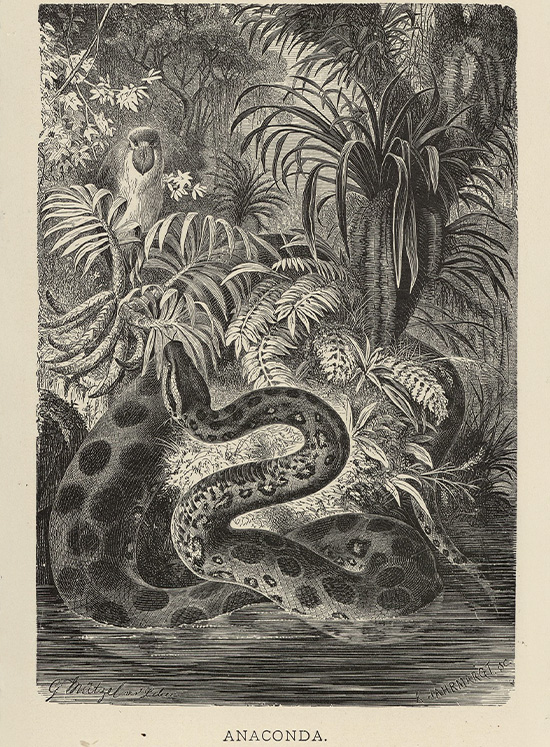

Anaconda

“OUR LIVING WORLD,” A NATURAL HISTORY BY REV. J. G. WOOD. REVISED AND ADAPTED TO AMERICAN ZOOLOGY BY JOSEPH B. HOLDER. VOL.V NEW YORK: SELMAR HESS, 1898.

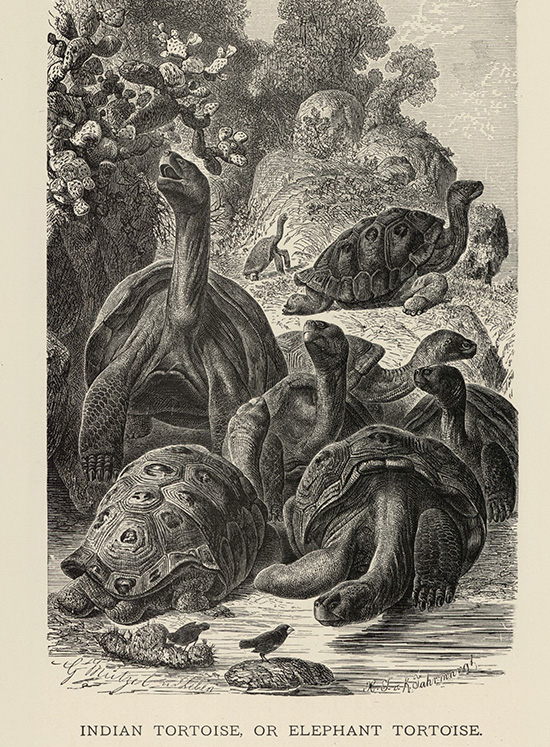

Indian Tortoise

“OUR LIVING WORLD,” A NATURAL HISTORY BY REV. J. G. WOOD. REVISED AND ADAPTED TO AMERICAN ZOOLOGY BY JOSEPH B. HOLDER. VOL.V NEW YORK: SELMAR HESS, 1898.

What aspects of biodiversity loss most expose us to the emergence and spread of new epidemics?

The “biodiversity crisis” does not just involve the extinction of species; it also involves the transfer of some kinds of species—what I called “weedy species” of both animals and plants and other creatures, in my 1998 essay “Planet of Weeds”—from their native ranges into other places, other parts of the world, other ecosystems. In other words, the problem of invasive species and “exotic” species, changing their distributional ranges, especially with the conscious or inadvertent aid of human actions.

One small example: climate change is allowing tropical species of mosquitoes, ticks, and other arthropods that carry (as “vectors”) human diseases to expand their geographical distributions toward the poles—out of the tropics, into subtropical and tropic regions, as tempe-ratures in those regions increase. The return of yellow fever and malaria to parts of Italy represent some of the consequences.

Which virus today holds the highest pandemic potential? And how can stronger biodiversity protection help reduce the risk of its spread?

The leading candidate for the next pandemic virus is the H5N1 avian influenza virus—or, to be more precise, some version of that virus containing the H5 genetic component, possibly in combination (by the sort of swapping of gene segments that influenzas routinely perform) with another influenza bearing a different N segment. Strains of that bird flu virus are now present in wild birds all over the world, domestic poultry all over the world, dairy cows in the US, and are also intermittently breaking out in and killing individuals of many other sorts of mammals. It will probably take just a handful of mutations, in one variant, to make that virus a pandemic killer of humans. And strains of that virus are presently mutating trillions of times per day, in the many animal hosts I’ve just mentioned. The roulette wheel is spinning, as I’ve said elsewhere, and the more it spins, the more likely that the ball will land on Black 13: pandemic bird flu.

Measures of biodiversity protection that protect ecological complexity and relative stability, rather than continuing disruption of highly diverse ecosystems for resource exploitation, will in general reduce the threat of spillovers, outbreaks, and pandemics.

In an interview, you once said that «we’re heading toward a more boring planet». Why?

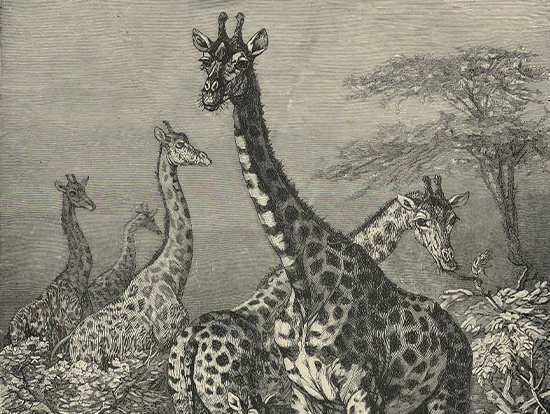

Yes, I’ve said that we are (because of catastrophic losses of biological diversity) heading toward a planet that’s more boring, lonely, and ugly than the planet we inherited from our ancestors. Imagine an Earth, in 100 years, on which (because of technological marvels) we have 10 billion people, and (I said imagine) every human is well-fed and healthy. But there are no polar bears. There are no gorillas. There are no rhinoceroses or elephants or giraffes. There are no giant moths. There are no hummingbirds. There are no hornbills. There are no swallowtail butterflies. There are no eagles. There are no whooping cranes. There are no wolves. There are no bears. Not in the wild, anyway—because there is no wild. There are only some captive animals in zoos, pathetic reminders of the past. That’s boring. Sad. If it’s the future, I’m glad I won’t live to see it.

But I’m not resigned. That’s the future we fight against. We need to say No, and act on that No. We want beauty and diversity and wonder, not just human survival.

Do you believe that a multidisciplinary approach and greater integration across fields could be (one of) the most effective tool to mitigate the climate crisis and protect public health from future viral threats?

Yes. Starting when children are young: teach them—allow them to discover—that science and literature and music and art and technology are all inter-tangled facets of the one truly beautiful thing that human beings have contributed to this planet: culture.

Is there a journey you haven’t taken yet, but consider essential to enrich your remarkable wealth of knowledge?

I haven’t yet been Antarctica, Rajasthan, or Assisi.

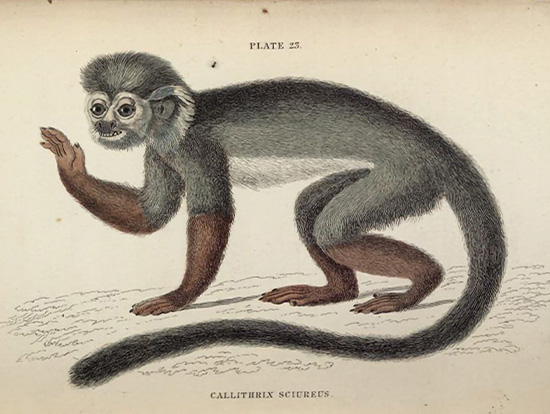

Callithrix Sciureus

“THE NATURAL HISTORY OF MONKEYS”. ILLUSTRATED BY THIRTY-ONE PLATES, NUMEROUS WOOD-CUTS, AND A PORTRAIT AND MEMOIR OF BUFFON, BY SIR WILLIAM JARDINE, BART. EDINBURGH: W.H. LIZARS, AND STIRLING, AND KENNEY [ETC.], 1833.

Giraffe

“OUR LIVING WORLD,” A NATURAL HISTORY BY REV. J. G. WOOD. REVISED AND ADAPTED TO AMERICAN ZOOLOGY BY JOSEPH B. HOLDER. VOL.II. NEW YORK: SELMAR HESS, 1898.

David Quammen

Writer and science communicator. He has written for National Geographic, Harper’s, Rolling Stone, and The New York Times. He is the author of numerous books, including the international bestseller “Spillover”.

Fabrizio Fasanella

Journalist at Linkiesta, where he covers urban topics, climate, environment, and mobility. Formerly at Torcha and The Good Life Italia, with contributions to QN, Fondazione Feltrinelli, and Panorama.