The opening of the Suez Canal and the “Trieste system”

In the sixteenth century, the Venetians dreamt of making the world smaller by connecting the Gulf of Suez to the Mediterranean so as not to have to sail around Africa. In the Napoleonic era, the French dreamt of the same thing. And it was the “Great Frenchman” Ferdinand de Lesseps who took charge of making the dream reality. Between 1854 and 1856, Lesseps had obtained permission from the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan to build a canal open to ships of all nations. The construction company, founded in 1859, was jointly owned and supported by France and Austria. But Trieste, then part of the Austrian Empire, also played a key role in the story, through Pasquale Revoltella.

Born in Venice to a modest family, Pasquale soon moved to Trieste. After losing his father, he started work very young, showing a great spirit of initiative.

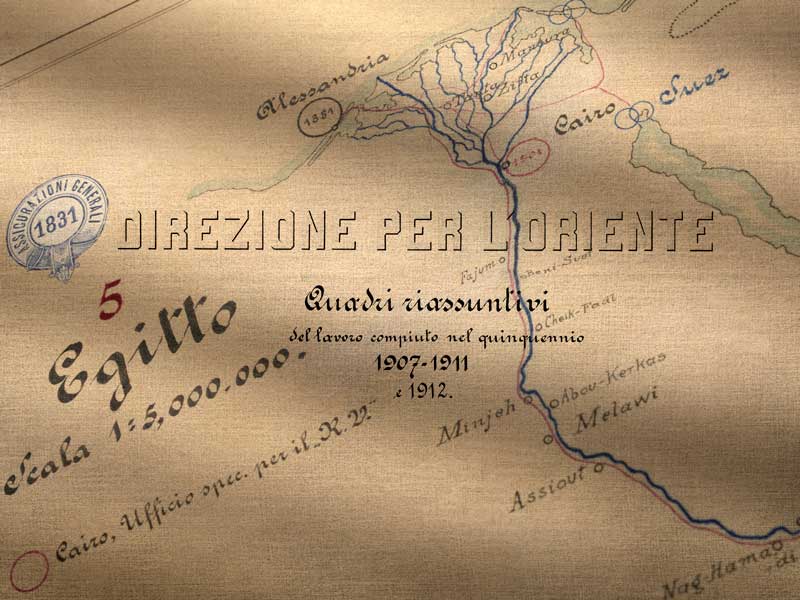

Map of the region of operation under the East Department of Generali (1912) Assicurazioni Generali Historical Archive ph. Massimo Gardone

In the mid-nineteenth century, he was one of the most respected businessmen in the city. A financier, town councillor, stock exchange deputy, philanthropist and art collector (his collection continues to grow even today through the bequest to the Revoltella Museum in Trieste), director of Generali, he had influential friends, like Baron de Bruck, founder of Lloyd Austriaco and Vienna’s future minister of commerce and finance.

Having become Vice President of the Suez Canal Company, Revoltella poured all his determination into the project. The opening of the canal was his dream too, tied to a personal vision for the development of Trieste and the port, which was experiencing a stagnant business period at the time. On the one hand, the costs of the Italian-Austrian conflicts had unsettled the economic climate; on the other, the lack of railway connections with the hinterland had moved the hub of trade elsewhere. So Revoltella set sail for Egypt, where he met prominent people and expanded his collections with amulets, scarabs, and a canopic jar. But, above all, he emphasised Trieste’s role in the new economic geography.

He died shortly before the inauguration of the canal, which took place in 1869 with formal celebrations. Representing Trieste was Giuseppe de Morpurgo, a prominent entrepreneur in the city, Vice-Chairman of the city council and the Chamber of Commerce, and also a director of Generali. When Emperor Franz Joseph urged the city to be the first to reap the benefits of the initiative, Morpurgo reminded him that the central government also had to play its part, building the railway it still lacked. During his stay, he wrote a report for the Chamber of Commerce, extolling the benefits of the canal, and sent his wife and children long letters with his impressions of his journeys and the curiosities of a world so close yet so exotic.

Revoltella’s and Morpurgo’s efforts were not in vain. After Suez, Trieste’s banking system was boosted, as was the influx of Austro-German capital into local businesses. Trieste’s trade expanded and the city was populated at a spectacular rate.

After Suez, as Trieste’s middle class grew and the city’s cosmopolitanism seemed to guarantee lasting economic success, Generali expanded its markets around the globe. Its partnership with Lloyd Austriaco continued: in the 1880s, its agents promoted Generali policies in the ports along the routes crossed by the shipping company. Thus, Generali’s expertise was shared with the rest of the world, facilitating the dynamics of internationalisation in the insurance sector.

The change was staggering, also in terms of figures: in 1870, when the Suez canal opened completely, 400 ships passed through it (1 and a half per day), 3,444 passed through in 1900 (10 per day), and 5,085 in 1913 (15 per day).

Over the years, Generali established representatives along the new lines of commercial expansion: on one hand the Mediterranean area, and on the other, the major overseas ports.

Generali was aboard cargo ships along routes across the world. Even in the 1950s, their cupboards still smelled of tea, coffee, liquorice, curry, and cardamom, and sailing or steamship logbooks for Shanghai and Hong Kong were still to be found in their attics.